By Dana Gornall

I’ve been reading a lot about Buddhism.

At first, it was general books about how it all worked and who the Buddha was. Later it became more about the philosophy of it all and then it was about how to practice as an average person—an everyday mom or dad or working adult—in the everyday world.

Recently I read a passage in Mark Epstein’s The Trauma of Everyday Life, in which he talks about an experience he had when he was traveling to Asia with some of his American Buddhist teachers. While visiting Ajahn Chah’s monastery, they had the opportunity to meet with Ajahn Chah, himself. In a poignant moment, Chah motioned to a glass on the table and told them that he loved that glass. He loved the way it held water, the way the sunlight reflected off of it, and the sound it made when he tapped it. He then explained that someday, the wind would most surely knock it off the table or the shelf and it would break. He understood, that in a way, this glass was already broken—already gone—and so he loved it even more because each moment with this glass was precious.

While this may seem like an odd way to think about things, there is so much truth to this story. It made me stop reading, sit back and think.

When I was a child, I had a large array of stuffed animals and dolls. Looking back now, I couldn’t tell you how many I had, but I know there were my favorites and each had a name and place in my room. I had this wild imagination, and I used to think that there was life in my toys—like the movie Toy Story. It was important to me that they were treated kindly, and each one would always be set back in the place it belonged.

Often on rainy days, or even the sunny ones, I would pull out my chalkboard and prop up every stuffed animal and doll onto my bed. I would become the teacher and play school. Sometimes I would carefully wrap up a baby doll into a blanket, gingerly placing her into my small baby buggy. I’d walk up and down the street, or set her up in my toy Raggedy Ann high chair and pretend to feed her breakfast or lunch.

My things held value and life, and I was very attached to them.

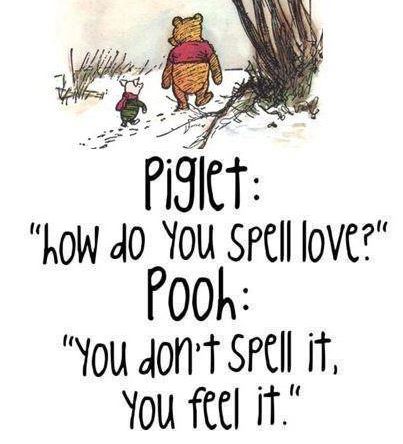

Then there was Pooh. A worn and faded yellow teddy bear, with one eyebrow missing and nose misshapen and pushed to the side, he was given to me when I was one year old and accompanied me every single night. My arm curled over his small body, my head and nose pressed into his pilled fabric, I would lie in bed with thoughts drifting in and out, dreams of someday floating just above me and sometimes nightmares trailing through, pulling me out of restless sleep.

He was my companion, my friend.

And I grew. I went to high school and then college and one day someone asked me to marry him and we did all of the typical things people do when they are planning a celebration such as that. When my family threw a bridal shower for me, the idea came about that we would have a tea party theme and display some of my childhood toys—not all, but my favorites like the baby dolls I so carefully wrapped up in blankets and walked up and down the street in baby buggies, and the animals I propped up in neat lines and played school.

And of course Pooh—my steady companion on so many nights.

The day came and there were so many people milling about. There were presents and food, much talking and of course there was tea. There were games to be played and pictures to be taken and many of my family and friends and friends of friends commented on the table that displayed all of my favorite toys and stuffed animals.

How cute, they said. How sweet, they remarked. I smiled and nodded and told some of them stories about walks and high chairs and pretend breakfasts and lunches.

The day was soon finished and all of the things had been gathered up to take home. Feeling tired and worn, we left everything in piles around the room after getting back to my parents’ house. It wasn’t until the next day that I discovered they were gone.

Sorting through all of the bags and piles, I searched; at first calmly, in a half-tired, half-interested sort of way, and then more and more anxiously. My toys—the baby dolls I had gingerly wrapped up in blankets and walked up and down the street with, the animals I had neatly propped up onto the bed, and especially, my Pooh—were all gone.

Tracing backward, the only thing we could figure out was that perhaps someone had placed them into a bag, and perhaps another person mistook it for trash and threw it into the church dumpster. Of course, we trekked back to the church, and looked around. We made phone calls to family and to friends and even to friends of friends until it was clear that these pieces of my childhood were truly never coming back.

There was some sadness at this thought, and yet also even back then, there was acceptance.

My life was changing. I was an adult. I was entering a new phase of my life and had no need for baby dolls and animals, including my beloved Pooh. Even back then, as a little girl while playing with my toys, in some sense they were already gone—would be gone one day.

They were already broken.

There are so many things we hold dear. We shine up our cars, we build shelves for our books and line them up by theme, or title or size, we shove our cell phones into our back pockets and place them on our nightstands when we sleep.

We reach out and touch our loved ones. We sit and we talk and we laugh with our friends. We text the people we don’t see often and we call our grandmas and grandpas from time to time. We watch our children as they sleep and we tell people how fast time flies.

And we know that each moment is precious and so very full of life and we, of course, are attached. It is only this moment now that we can hold because it is always fleeting and one day will be gone. So we can only love this moment, this thing, this person.

Love it, even when it is already broken.

Photo: (source)

Editor: Alicia Wozniak

Comments

- The Power of Choice When Things Feel Out of Your Control (and What the Buddha Got Right About It) - July 21, 2023

- Why That Productivity App Won’t Fix Your Overwhelmed Mind - July 11, 2023

- Chasing Sunsets: A Story about a Dog - January 19, 2023