So, I have lived two very different lifestyles as a practicing Zen Buddhist in the span of a year, and neither one of them seemed quite “right.” I’m starting to think that maybe the lifestyle isn’t the problem—maybe the problem is me.

By Sensei Alex Kakuyo

I have a job in corporate America working as a business analyst.

The money is good and the hours are great. My coworkers are reasonably friendly, and my stress level rarely goes above a 6 on a scale of 1-10. In short, I have very little to complain about, but that doesn’t stop me from feeling like my job is interfering with the real work that I should be doing.

Every day, I sit down in my cubicle and begin my daily tasks. As the day progresses, a feeling of dark discontent grows in my stomach. Eventually, the feeling in my stomach reaches my brain and becomes a question: Why am I wasting time responding to email when I should be focused on my spiritual practice?

To be fair, this feeling of discontent isn’t new.

I felt the same way when I worked my last mid-level corporate gig, and I responded by quitting my job and going to work on organic farms for eight months. It was a great experience. Seriously, you can’t spend eight months pulling weeds and shoveling manure each day without learning some things about yourself. But I felt like I was hiding from the “real” world, so I came back to conventional society, and traded in my work boots for dress shoes. Now that I’m here, the only thing I seem to do is reminisce about what life was like on the road.

So, I have lived two very different lifestyles as a practicing Zen Buddhist in the span of a year, and neither one of them seemed quite “right.” I’m starting to think that maybe the lifestyle isn’t the problem—maybe the problem is me. More specifically, maybe the problem is what I think it means to walk a spiritual path.

Case in point, when I envision spiritual practice there are two images that come to mind. The first would involve life in a monastery. I’ve always had a deep love for ritual and sacred spaces. Cloistered environments with long histories and strict rules of conduct have always given me a feeling of safety, and the desire for that feeling has only become stronger as I’ve aged. Even as I type this, the idea of waking up every day in a temple that is hundreds of years old and dedicating every waking moment to the practice of the dharma brings a smile to my face.

I have no illusions that it would be an easy life. All of the stories that I’ve read paint a picture of hard manual labor, strict adherence to a schedule and very few creature comforts for people who are novitiates in a temple. But in this sensory overloaded world of instant gratification and bad reality TV shows I think there is a certain beauty in learning to do without.

The next image that comes to mind involves me living the life of a hermit monk. Home-leaving is a time honored tradition in many schools of Buddhism. In fact, one of things that helped spark my interest in Zen practice was watching the documentary, Amongst White Clouds and learning about the hermit monk tradition in Zen Buddhism. The monks in the documentary have almost nothing, but the peacefulness and real happiness that each of them exudes is incredible to see. I’d gladly trade in my few worldly possessions and live in a hut if I could have what they have.

The Chinese poet Li Po did a beautiful job of describing this tradition when he said:

You ask me why I dwell amidst these jade-green hills.

I smile. No words can describe the stillness in my heart.

Peach blossoms drift away upon stream waters

deep with mystery.

For I live in the other world,

the one that lives beyond the whim of men

Seriously, I can’t read that poem without wanting to drop everything, follow Li Po’s example, and spend the rest of my life in the mountains. But here’s the catch, I’m not Li Po. And I can’t live his life anymore than he can live mine.

Zen teaches us that the Buddha’s path is identical to the Buddha’s life. Our ordinary, everyday existence is our spiritual path whether we want it to be or not. So when I describe my “ideal” spiritual practice, what I’m really describing is the life I wish I could live.

My fantasies about living in a monastery or retreating to a hermitage are beautiful, but their beauty comes wrapped in a web of desire. And desire always leads to despair. I experience that despair everyday when I sit in my cubicle wishing that I could live the life of a monk or a hermit.

Despite my misgivings, I’m beginning to realize that real spiritual practice consists of being content with what life gives me in each passing moment.

In fact, the more I think about it, the more I realize that it’s a mistake to lust after the spiritual practice that others enjoy. Rather, it’s better to focus on being a good student of my own spiritual/ life practice and learning everything it has to teach me.

I wanted life to give me a monastery for my training, but it’s given me an office building instead. What can I learn from that?

I asked to wear robes as part of my practice, but life gave me a shirt and tie. Why did it do that? I don’t know.

Honestly, I have no idea what being a business analyst can teach me about Zen, but I’m willing to learn, and I’m sure that life has no end of things to teach me.

I wanted life to give me a monastery for my training, but it's given me an office building instead. ~ Sensei Alex Kakuyo Click To Tweet

*originally published here and reprinted with author’s permission.

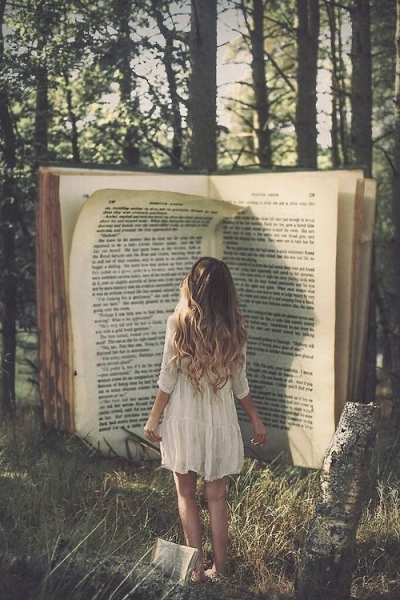

Photo: (source)

Editor: Dana Gornall

Comments

- Saving the World is Hard (But We Can Start by Making the Bed) - January 9, 2024

- No Shortcuts to Inner Peace - November 28, 2023

- Why I am Not a Minimalist (anymore) - November 8, 2023

I am a Buddhist teacher in a non Zen tradition. And a Business Analyst in a corporate environment. Following the Buddha dharma there is our practice. It is harder than being separated from the world, filled with distraction. But a real place to live the dharma and thereby teach and save all beings. Not by being more Zen or trying to be better than others, but by following the middle path and sharing that with everyone. Peace,

did life give you that office building or did you choose it?